The Case for Humanity: An Approach to Programming Music

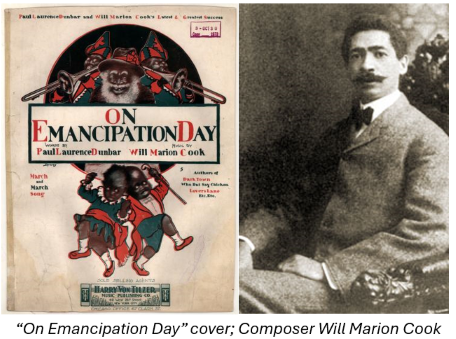

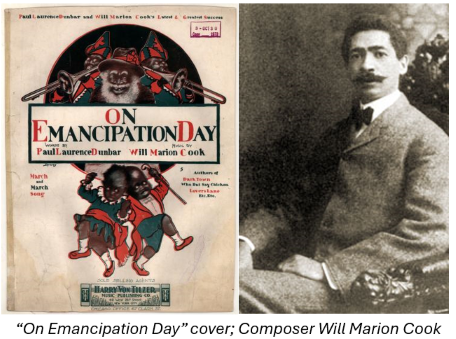

About two years ago, I taught a college music history class that included a unit on Black composers in the late 19

th and first half of the 20th century. I had planned to play and discuss the song “Emancipation Day” from

In Dahomey (1902), an all-Black Broadway revue by Will Marion Cook (1869-1944). Here is a

YouTube link to the song (not sung, but with full lyrics). Cook’s musical style was influenced by minstrel shows

[1] and ragtime. The song’s lyrics, by Black poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar, are in Black dialect of the period, and use terms, style, and characterization that in our time would be considered offensive by many listeners but which have also been praised by Dunbar scholar Addison Gayle, Jr. and poet Nikki Giovanni.

In preparing the class, I warned the students that they might be shocked at some of the language of the song. One student remarked that she did not want to hear it played. After her response, I described the work but did not play it. Since that day, I have rethought skipping the piece, and regretted my approach. If I were to teach the unit again, I would take a deeper dive into the cultural context of the song and its creators, and I would play it.

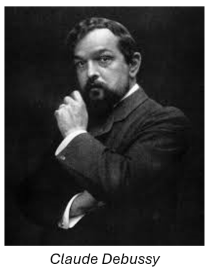

What are ways that a teacher/coach/conductor/programmer can approach works of music that make

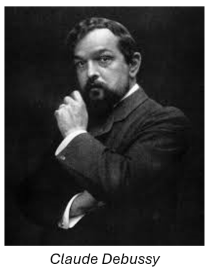

participants uncomfortable or offended? In first choosing a piece of music for a class or program, it must have either aesthetic or historical worth or both. If the piece is controversial, then discussing historical context is essential. Long ago, when I was more of a pianist than recorderist, I studied Claude Debussy’s charmingly humorous

Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk, the last piece in his

Children’s Corner solo piano suite (L. 113, 1908). The piece, one of Debussy’s most popular, has a ragtime feel and a very amusing parody of the love theme from Richard Wagner’s

Tristan und Isolde. Here is a

YouTube link to Debussy’s own performance via piano roll. What my teenaged self did not realize was that a Golliwogg was a late 19

th-century American Black children’s character based on minstrel-show imagery.

[2] Debussy’s young daughter Chouchou likely had a doll based on the character, and the original Durand edition (I own a copy!) features Debussy’s own illustration of a Golliwogg on the cover.

In the twentieth century, the term has been widely used as a racial slur; Paul Barton’s performance on YouTube changes the name to

Golli’s Cake-Walk and Black pianist Isata Kanneh-Mason simply calls it

Cakewalk on her fine video.

[3] Should the Debussy piece no longer be played? Just as the satirical

Tristan quotation makes no sense without explanation, so the caricature should be explained and its social context not forgotten. I was very surprised in looking at remarks accompanying the many YouTube recordings, that almost none mention the imagery! There is also little explanation of the cakewalk, an American dance from the mid-nineteenth century created by enslaved Blacks that may have embodied a slyly subversive exaggeration of the social dances of White plantation slave owners, an allusion that Debussy may not have been aware of.

This complex, difficult history and the humanity of the imagery cannot be allowed to disappear. This is why I don’t recommend bowdlerization, i.e. cutting out potentially offensive material, including changing the name of the music to avoid offense.

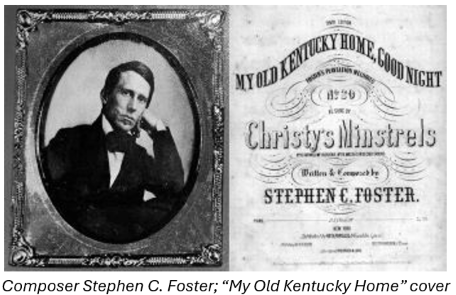

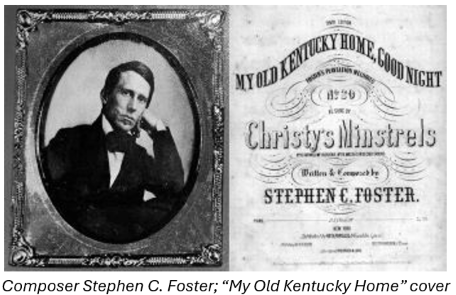

Consider the music of Stephen Foster (1826-1864), many of whose songs are still a living part of the American musical vernacular.

[4] Ken Emerson, rock critic and biographer of Stephen Foster,

[5] has stressed the complexity of approaching Foster’s legacy: As a northern White songwriter, Foster was hugely successful and influential, one of the first to support himself exclusively by publishing his songs; Foster himself was influenced by the music of enslaved southern Blacks, as well as by several European traditions. Many of his songs were written for and performed by White minstrel shows in blackface,

[6] and several Foster songs are in Black dialect. Paradoxically, one of Foster’s best known songs—“My Old Kentucky Home”—was apparently inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was lauded by Frederick Douglass as encouraging sympathy for enslaved Blacks, but also promoted and performed as a blackface minstrel show number, a use that is not surprisingly seen as racially offensive to modern sensibilities.

Here is a link to one of many YouTube performances.

If a recorder player searches for “Stephen Foster recorder arrangements,” many modern publications of Foster’s earworm melodies pop up. (Many of the original song prints are available free on IMSLP.) Is it okay to perform these? In my opinion, performing Foster’s plantation songs such as “Oh Susanna” or “My Old Kentucky Home” without historical background is insensitive and somewhat clueless to modern audiences both Black and White. However, programming arrangements of Foster’s music with attention paid to its historical context—social, political, and musical—can make for an informative and rewarding experience. The point is to not give in to mindless nostalgia, but to remember the human elements of the music—its composer and lyricist, those who influenced it, its performers, and those who heard it and who would now hear it.

Wendy Powers is an adjunct assistant professor at Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College of the City University of New York, teaching undergraduate and graduate music history and early music notation. She is a member of the planning committee and faculty member of the Amherst Early Music Festival and is co-director (with Valerie Horst) of the CityRecorder! workshop in New York City. She has a BS in music education from New York University and an MA and Ph.D in historical musicology from Columbia University. She served on the ARS Board as Treasurer from 2016-2024.

Wendy Powers is an adjunct assistant professor at Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College of the City University of New York, teaching undergraduate and graduate music history and early music notation. She is a member of the planning committee and faculty member of the Amherst Early Music Festival and is co-director (with Valerie Horst) of the CityRecorder! workshop in New York City. She has a BS in music education from New York University and an MA and Ph.D in historical musicology from Columbia University. She served on the ARS Board as Treasurer from 2016-2024.

participants uncomfortable or offended? In first choosing a piece of music for a class or program, it must have either aesthetic or historical worth or both. If the piece is controversial, then discussing historical context is essential. Long ago, when I was more of a pianist than recorderist, I studied Claude Debussy’s charmingly humorous Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk, the last piece in his Children’s Corner solo piano suite (L. 113, 1908). The piece, one of Debussy’s most popular, has a ragtime feel and a very amusing parody of the love theme from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Here is a

participants uncomfortable or offended? In first choosing a piece of music for a class or program, it must have either aesthetic or historical worth or both. If the piece is controversial, then discussing historical context is essential. Long ago, when I was more of a pianist than recorderist, I studied Claude Debussy’s charmingly humorous Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk, the last piece in his Children’s Corner solo piano suite (L. 113, 1908). The piece, one of Debussy’s most popular, has a ragtime feel and a very amusing parody of the love theme from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Here is a

Wendy Powers is an adjunct assistant professor at Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College of the City University of New York, teaching undergraduate and graduate music history and early music notation. She is a member of the planning committee and faculty member of the Amherst Early Music Festival and is co-director (with Valerie Horst) of the CityRecorder! workshop in New York City. She has a BS in music education from New York University and an MA and Ph.D in historical musicology from Columbia University. She served on the ARS Board as Treasurer from 2016-2024.

Wendy Powers is an adjunct assistant professor at Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College of the City University of New York, teaching undergraduate and graduate music history and early music notation. She is a member of the planning committee and faculty member of the Amherst Early Music Festival and is co-director (with Valerie Horst) of the CityRecorder! workshop in New York City. She has a BS in music education from New York University and an MA and Ph.D in historical musicology from Columbia University. She served on the ARS Board as Treasurer from 2016-2024.